Hegel über Platon 018

Parte de:

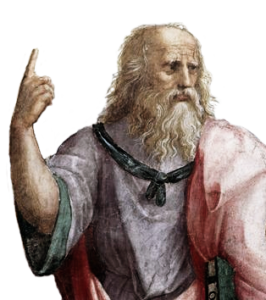

Lecciones de Historia de la Filosofía [Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie] / Primera parte: La Filosofía Griega [Erster Teil: Griechische Philosophie] / Sección Primera: de Tales a Aristóteles [Erster Abschnitt. Von Thales bis Aristoteles] / Capítulo 3: Platón y Aristóteles [Drittes Kapitel: Platon und Aristoteles] / A. Platón [A. Philosophie des Platon]

Tabla de contenidos

Vorlesungen im Atrium Philosophicum §18

Die Manier der Vorstellung hat Platon auch oft. Es ist einerseits populär, aber andererseits die Gefahr unabwendbar, daß man solches, was nur der Vorstellung angehört, nicht dem Gedanken, für etwas Wesentliches nimmt. Es ist unsere Sache, zu unterscheiden, was Spekulation, was Vorstellung ist. Kennt man nicht für sich, was Begriff, spekulativ ist, so kann man eine ganze Menge Theoreme aus den Dialogen ziehen und sie als Platonische Philosopheme ausgeben, die durchaus nur der Vorstellung, der Weise derselben angehören. Diese Mythen sind Veranlassung gewesen, daß viele Sätze aufgeführt werden als Philosopheme, die für sich gar nicht solche sind. Indem man aber weiß, daß sie der Vorstellung als solcher angehören, so weiß man, daß sie nicht das Wesentliche sind. So z.B. bedient sich Platon in seinem Timaios, indem er von der Erschaffung der Welt spricht, der Form, Gott habe die Welt gebildet, und die Dämonen hätten dabei gewisse Beschäftigungen gehabt (41); es ist ganz in der Weise der Vorstellung gesprochen. Wird dies aber für ein philosophisches Dogma Platons genommen, daß Gott die Welt geschaffen, daß Daimonien, höhere Wesen geistiger Art, existieren und bei der Welterschaffung Gottes hilfreiche Hand geleistet haben, so steht dies zwar wörtlich in Platon, und doch ist es nicht zu seiner Philosophie gehörig. Wenn [30] er von der Seele des Menschen sagt, daß sie einen vernünftigen und unvernünftigen Teil habe, so ist dies ebenso im allgemeinen zu nehmen; aber Platon behauptet damit nicht, daß die Seele aus zweierlei Substanzen, zweierlei Dingen zusammengesetzt sei. Wenn er das Lernen als eine Wiedererinnerung vorstellt, so kann das heißen, daß die Seele vor der Geburt des Menschen präexistiert habe. Ebenso wenn er von dem Hauptpunkte seiner Philosophie, von den Ideen, dem Allgemeinen, als dem bleibenden Selbständigen spricht, als den Mustern der sinnlichen Dinge, so kann man dann leicht dazu fortgehen, jene Ideen nach der Weise der modernen Verstandeskategorien als Substanzen zu denken, die im Verstande Gottes oder für sich, als selbständig, z.B. als Engel, jenseits der Wirklichkeit existieren. Kurz alles, was in der Weise der Vorstellung ausgedrückt ist, nehmen die Neueren in dieser Weise für Philosophie. So kann man Platonische Philosophie in dieser Art aufstellen, man ist durch Platons Worte berechtigt; weiß man aber, was das Philosophische ist, so kümmert man sich um solche Ausdrücke nicht und weiß, was Platon wollte. Wir haben jedoch nun zur Betrachtung der Philosophie des Platon selbst überzugehen.

Zum nächsten Fragment gehen

Praelēctiōnēs in Ātriō Philosophicō §18

Por tanto, para captar la filosofía de Platón a base de sus diálogos, es necesario que sepamos distinguir lo que es simple representación, sobre todo allí donde recurre a los mitos para exponer una idea filosófica, y lo que es la idea filosófica misma; sólo entonces es posible saber que lo que se refiere a la representación como tal, y no al pensamiento, no es lo esencial. En cambio, si no se conoce para sí lo que es concepto, lo que es especulativo, se expone uno inevitablemente al peligro de que, dejándose llevar por los mitos, se extraigan de los diálogos toda una serie de tesis y teoremas, viendo en ellos filosofemas platónicos, cuando en realidad no son tal cosa, sino simples representaciones. Así, por ejemplo, en su Timeo (p. 41 Steph., p. 43 Bekk.) se vale Platón de la forma de expresión que consiste en decir que el mundo fue creado por Dios y que a los demonios les fueron adjudicadas ciertas ocupaciones en relación con ello, lo que cae por entero dentro del campo de la representación. Pero esto no basta para que consideremos como un dogma filosófico de Platón la tesis de que Dios ha creado el mundo y de que existen seres superiores de carácter espiritual que ayudaron a Dios en aquella obra: es cierto que esto se halla literalmente expresado en un diálogo platónico, pero no por ello debemos creer que forme parte de su filosofía. Cuando Platón, a manera de representación, dice que el alma del hombre tiene una parte racional y una parte irracional, tampoco estas palabras deben tomarse sino con carácter general; Platón no pretende, con ello, afirmar filosóficamente que el alma se halle integrada por dos clases de sustancias, por dos clases de cosas. Cuando se representa el conocer, el aprender, como una reminiscencia, esto puede significar que el alma tuvo una existencia previa anterior al nacimiento del hombre. Y lo mismo cuando habla de lo que constituye el punto central de su filosofía, de las ideas, de lo general, como de lo sustantivo y permanente, de los verdaderos modelos de que las cosas sensibles son copias. Esto puede fácilmente llevarnos a ver en aquellas ideas, interpretándolas al modo de las modernas categorías intelectivas, una especie de sustancias existentes en la inteligencia de Dios, o para sí, como sustancias independientes, por ejemplo como ángeles, más allá de la realidad. En una palabra, los intérpretes modernos tienden a considerar directamente como filosofía todo lo que Platón expresa en el plano de la representación. Y no cabe duda de que, muchas veces, las propias palabras de Platón parecen autorizarnos a concebir de este modo la filosofía platónica; pero, si sabemos en qué consiste realmente lo filosófico no nos preocuparemos de tales expresiones y sabremos lo que en verdad quería y buscaba Platón.

Perge ad sequēns caput

Perge ad initium paginae huius

Lectures at the Atrium Philosophicum §18

In order to gather Plato’s philosophy from his dialogues, what we have to do is to distinguish what belongs to ordinary conception — especially where Plato has recourse to myths for the presentation of a philosophic idea — from the philosophic idea itself; only then do we know that what belongs only to the ordinary conception, as such, does not belong to thought, is not the essential. But if we do not recognize what is concept, or what is speculative, there is inevitably the danger of these myths leading us to draw quite a host of maxims and theorems from the dialogues, and to give them out as Plato’s philosophic propositions, while they are really nothing of the kind, but belong entirely to the manner of presentation. Thus, for instance, in the Timaeus Plato makes use of the form, God created the world, and the daemons had a certain share in the work; this is spoken quite after the manner of the popular conception. If, however, it is taken as a philosophic dogma on Plato’s part that God made the world, that higher beings of a spiritual kind exist, and, in the creation of the world, lent God a helping hand, we may see that this stands word for word in Plato, and yet it does not belong to his philosophy. When in pictorial fashion he says of the soul of man that it has a rational and an irrational part, this is to be taken only in a general sense; Plato does not thereby make the philosophic assertion that the soul is compounded of two kinds of substance, two kinds of thing. When he represents knowledge or learning as a process of recollection, this may be taken to mean that the soul existed before man’s birth. In like manner, when he speaks of the central point of his philosophy, of Ideas, of the Universal, as the permanently self-existent, as the patterns of things sensible, we may easily be led to think of these Ideas, after the manner of the modern categories of the understanding, as substances which exist outside reality, in the Understanding of God; or on their own account and as independent — like the angels, for example. In short, all that is expressed in the manner of pictorial conception is taken by the moderns in sober earnest for philosophy. Such a representation of Plato’s philosophy can be supported by Plato’s own words; but one who knows what Philosophy is, cares little for such expressions, and recognizes what was Plato’s true meaning.

Go to the next fragment