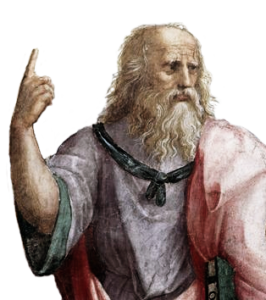

Hegel über Platon 017

Parte de:

Lecciones de Historia de la Filosofía [Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie] / Primera parte: La Filosofía Griega [Erster Teil: Griechische Philosophie] / Sección Primera: de Tales a Aristóteles [Erster Abschnitt. Von Thales bis Aristoteles] / Capítulo 3: Platón y Aristóteles [Drittes Kapitel: Platon und Aristoteles] / A. Platón [A. Philosophie des Platon]

Tabla de contenidos

Vorlesungen im Atrium Philosophicum §17

Von einfachen Begriffen spricht Platon so: »Ihre letzte Wahrheit ist Gott; jene sind abhängige, vorübergehende Momente, ihre Wahrheit haben sie in Gott«, und von diesem spricht er zuerst; so ist er eine Vorstellung.

Um die Philosophie Platons aus seinen Dialogen aufzufassen, muß das, was der Vorstellung angehört, insbesondere wo er für die Darstellung einer philosophischen Idee zu Mythen seine Zuflucht nimmt, von der philosophischen Idee selbst unterschieden werden, – und diese freie Weise des Platonischen Vortrags, von den tiefsten dialektischen Untersuchungen zur Vorstellung und Bildern, zur Schilderung von Szenen der Unterredung geistreicher Menschen, auch von Naturszenen überzugehen.

Die mythische Darstellung der Philosopheme wird von Platon gerühmt; dies hängt mit der Form seiner Darstellung zusammen. Er läßt den Sokrates von gegebenen Veranlassungen ausgehen, von den bestimmten Vorstellungen der Individuen, von dem Kreise ihrer Ideen; so geht die Manier der Vorstellung (der Mythus) und die echt spekulative durcheinander. Die mythische Form der Platonischen Dialoge macht das Anziehende dieser Schriften aus, aber es ist eine Quelle von Mißverständnissen; es ist schon eins, wenn man diese Mythen für das Vortrefflichste hält. Viele Philosopheme sind durch die mythische Darstellung nähergebracht; das ist nicht die wahrhafte Weise der Darstellung. Die Philosopheme sind Gedanken, müssen, um rein zu sein, als solche vorgetragen werden. Der Mythus ist immer eine Darstellung, die sich sinnlicher Weise bediene, sinnliche [29] Bilder hereinbringt, die für die Vorstellung zugerichtet sind, nicht für den Gedanken; es ist eine Ohnmacht des Gedankens, der für sich sich noch nicht festzuhalten weiß, nicht auszukommen weiß. Die mythische Darstellung, als älter, ist Darstellung, wo der Gedanke noch nicht frei ist: sie ist Verunreinigung des Gedankens durch sinnliche Gestalt; diese kann nicht ausdrücken, was der Gedanke will. Es ist Reiz, Weise anzulocken, sich mit Inhalt zu beschäftigen. Es ist etwas Pädagogisches. Die Mythe gehört zur Pädagogie des Menschengeschlechts. Ist der Begriff erwachsen, so bedarf er derselben nicht mehr. Oft sagt Platon, es sei schwer, sich über diesen Gegenstand auszulassen, er wolle daher einen Mythus aufstellen; leichter ist dies allerdings.

Praelēctiōnēs in Ātriō Philosophicō §17

Platón afirma, refiriéndose a los conceptos simples [einfachen Begriffen], que «su última verdad está en Dios; estos [los conceptos simples] son momentos transitorios dependientes cuya verdad última debe buscarse en Dios»; al hablar primeramente de éste, lo reduce a una mera idea [Vorstellung].

Para poder interpretar la filosofía de Platón en sus diálogos, especialmente cuando ésta se refugia en mitos para la representación de una idea filosófica, debemos distinguir lo que pertenece a la imaginación y a la idea filosófica propiamente dicha. Debemos acostumbrarnos a este modo libérrimo del discurso platónico que oscila de las más profundas investigaciones dialécticas a la imaginación e imágenes, de la descripción de escenas de las conversaciones de los más sesudos interlocutores a escenas de la naturaleza.

Platón sublima la representación mítica de ideas filosóficas, esto está relacionado con la forma de su representación. En sus escritos permite al personaje de Sócrates que parte de unas circunstancia dadas, se mueva a las ideas específicas de sus interlocutores al círculo de sus ideas. Con ello el estilo de la (el mito) y el estilo genuinamente especulativo se confunden. Por tanto, por mucho que se ensalce la exposición mítica de los filosofemas platónicos y por mucho que esto constituya el encanto de sus diálogos, es innegable que es, al mismo tiempo, una fuente de equívocos y oscuridades, los cuales empiezan ya cuando se considera estos mitos como lo mejor de la doctrina de Platón. Es cierto que muchos filosofemas resultan más fáciles de comprender gracias a la exposición mítica, pero esto no quiere decir que sea éste el verdadero modo de exponer la filosofía; los filosofemas son pensamientos que, para ser puros, deben exponerse como tales y no de otro modo. El mito es siempre una exposición mezclada, como todas las exposiciones antiguas, con imágenes dirigidas a los sentidos y aderezadas para la representación, y no para el pensamiento; lo cual no indica sino la impotencia del pensamiento mismo, que aún no sabe andar sin andaderas y que no es aún, por tanto, un pensamiento libre. El mito forma parte de la pedagogía del género humano, en cuanto que la induce y la tienta a ocuparse del contenido de las cosas; pero, como impurificación que es del pensamiento mediante formas y figuras relacionadas con los sentidos, no puede expresar lo que el pensamiento quiere. El concepto adulto no necesita ya apoyarse en el mito. Platón dice con frecuencia que es difícil expresar tal o cual objeto y que, por ello, recurrirá a la ayuda de un mito; y no cabe duda de que esto es más fácil.

Perge ad initium paginae huius

Lectures at the Atrium Philosophicum §17

Plato speaks of simple concepts as follows: “Their ultimate truth is God; those are dependent, transitory moments, they have their truth in God,” and in this first mention of God by Plato, He is made a mere idea

In order to understand Plato’s philosophy from his dialogues, what belongs to the imagination, especially where he takes refuge in myths for the representation of a philosophical idea, must be distinguished from the philosophical idea itself – and this free manner of Plato’s discourse, from the deepest dialectical investigations to imagination and images, to the description of scenes of the conversation of intelligent people, also of scenes from nature.

Plato praises the mythical representation of philosophical ideas; this is connected with the form of his representation. He lets Socrates start from given circumstances, from the specific ideas of individuals, from the circle of their ideas; thus the manner of representation (the myth) and the genuinely speculative are confused. However much, therefore, Plato’s mythical presentation of Philosophy is praised, and however attractive it is in his Dialogues, it yet proves a source of misapprehensions; and it is one of these misapprehensions, if Plato’s myths are held to be what is most excellent in his philosophy. Many propositions, it is true, are made more easily intelligible by being presented in mythical form; nevertheless, hat is not the true way of presenting them; propositions are thoughts which, in order to be pure, must be brought forward as such. The myth is always a mode of representation which, as belonging to an earlier stage, introduces sensuous images, which are directed to imagination, not to thought; in this, however, the activity of thought is suspended, it cannot yet establish itself by its own power, and so is not yet free. The myth belongs to the pedagogic stage of the human race, since it entices and allures men to occupy themselves with the content; but as it takes away from the purity of thought through sensuous forms, it cannot express the meaning of Thought. When the Notion attains its full development, it has no more need of the myth. Plato often says that it is difficult to express one’s thoughts on such and such a subject, and he therefore will employ a myth; no doubt this is easier.