Hegel über Platon 016

Parte de:

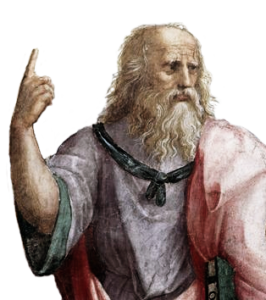

Lecciones de Historia de la Filosofía [Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie] / Primera parte: La Filosofía Griega [Erster Teil: Griechische Philosophie] / Sección Primera: de Tales a Aristóteles [Erster Abschnitt. Von Thales bis Aristoteles] / Capítulo 3: Platón y Aristóteles [Drittes Kapitel: Platon und Aristoteles] / A. Platón [A. Philosophie des Platon]

Tabla de contenidos

Vorlesungen im Atrium Philosophicum §16

Dies in Beziehung aufs Auffassen betrachtet, so geschieht es, um dieser beiden Umstände willen, daß entweder zuviel oder zuwenig in Platons Philosophie gefunden wird. α) Zuviel finden die Älteren, sogenannten Neuplatoniker, welche αα) teils, wie sie die griechische Mythologie allegorisierten, sie als einen Ausdrucks von Ideen darstellten (was die Mythen allerdings sind), ebenso die Ideen in den Platonischen Mythen erst herausgehoben, wodurch sie die Mythen erst zu Philosophemen machten; denn darin besteht das Verdienst der Philosophie, daß das Wahre in der Form des Begriffes ist, – ββ) teils was in der Form des Begriffes bei Platon ist, so für den Ausdruck des absoluten Wesens (die Wesenlehre im Parmenides für Erkenntnis Gottes) nahmen, daß Platon selbst es nicht davon unterschieden habe. Es ist in den Platonischen reinen Begriffen nicht die Vorstellung als solche aufgehoben oder nicht gesagt, daß diese Begriffe ihr Wesen sind, oder sie sind mehr nicht als eine Vorstellung für Platon, nicht Wesen. β) Zuwenig die Neueren besonders, denn diese hingen sich vorzüglich an die Seite der Vorstellung, sahen Realität in der Vorstellung. Was in Platon [28] Begriffenes oder rein Spekulatives vorkommt, gilt ihnen für ein Herumtreiben in abstrakten logischen Begriffen oder für leere Spitzfindigkeiten, dagegen dasjenige als Philosophem, was in der Weise der Vorstellung ausgesprochen ist. So finden wir bei Tennemann (Bd. II, S. 376) und anderen eine steife Zurückführung der Platonischen Philosophie auf die Formen unserer vormaligen Metaphysik, z.B. der Ursachen, der Beweise vom Dasein Gottes.

Praelēctiōnēs in Ātriō Philosophicō §16

Decimos esto, en lo que se refiere al modo de concebir de la filosofía platónica, con vistas a los que tienden a creer que se contiene en ella demasiado o demasiado poco. Tienden a encontrar en ella α) demasiado los autores antiguos, los llamados neoplatónicos, los cuales, αα) en parte, al alegorizar la mitología griega y presentarla como una expresión de Ideas —lo que, en realidad, son los mitos—, destacan también las Ideas contenidas en los mitos platónicos, convirtiendo con ello estos mitos en filosofemas (pues el mérito de la filosofía consiste única y exclusivamente en presentar lo verdadero bajo la forma del concepto) y, ββ) en parte, toman como expresión del ser absoluto [des absoluten Wesens] lo que en Platón se presenta bajo la forma del concepto —por ejemplo, toman la teoría del ser [die Wesenlehre] expuesta en el Parménides como el conocimiento de Dios—, como si Platón no se preocupara de distinguir una cosa de la otra. Sin embargo, en los conceptos platónicos puros no aparece superada la idea como tal: o bien no se dice que estos conceptos sean su ser [Wesen], o no son, para Platón, otra cosa que la Idea, y no su ser [Wesen]. Otros intérpretes, principalmente los modernos, tienden a encontrar, en Platón, demasiado poco; estos autores se aferran, principalmente, al lado de la representación, y ven en ella una realidad. Lo que hay en Platón de comprendido conceptualmente o de puramente especulativo es considerado por ellos como un devaneo en torno a conceptos lógicos abstractos o como una serie de vacuas sutilezas, tendiendo, en cambio, a ver filosofemas en lo que Platón expone solamente como representaciones. Así, en Tennemann (t. II, p, 376) y en otros autores modernos nos encontramos con una rígida reducción de la filosofía platónica a las formas de nuestra anterior metafísica, por ejemplo, a las de las pruebas de la existencia de Dios.

Perge ad initium paginae huius

Lectures at the Atrium Philosophicum §16

Looking at this as it bears on the question of how Plato’s philosophy is to be apprehended, we find, owing to these two circumstances, that either too much or too little is found in it. α) Too much is found by the ancients,, the so-called Neoplatonists, αα) who sometimes dealt with Plato’s philosophy as they dealt with the Greek mythology. This they allegorized and represented as the expression of Ideas — which the myths certainly are — and in the same way they first raised the Ideas in Plato’s myths to the rank of philosophemes; for the merit of Philosophy consists alone in the fact that truth is expressed in the form of the concept. ββ) Sometimes, again, they took what with Plato is in the form of the concept for the expression of Absolute Being [des absoluten Wesens] — the theory of Being [die Wesenlehre] in the Parmenides, for instance, for the knowledge of God — just as if Plato had not himself drawn a distinction between them. But in the pure concepts of Plato the Idea as such is not abolished; either it is not said that these concepts constitute its reality, or they are to Plato no more than an idea, and not reality [Wesen]. β) Again, we certainly see that too little is found in Plato by the moderns in particular; for they attach themselves pre-eminently to the side of the imagination, and see in it reality. What in Plato relates to the concept, or what is purely speculative, is nothing more in their eyes than roaming about in abstract logical concepts, or than empty subtleties, whereas what is expressed in the manner of the imagination is regarded as philosophical. Thus we find in Tennemann (Vol. II. p. 376) and others an obstinate determination to lead back the Platonic Philosophy to the forms of our former metaphysic, e.g. to the proof of the existence of God.