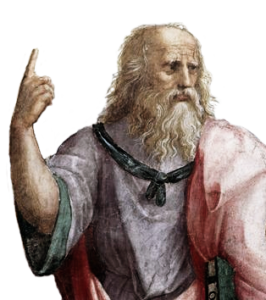

Hegel über Platon 012

Parte de:

Lecciones de Historia de la Filosofía [Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie] / Primera parte: La Filosofía Griega [Erster Teil: Griechische Philosophie] / Sección Primera: de Tales a Aristóteles [Erster Abschnitt. Von Thales bis Aristoteles] / Capítulo 3: Platón y Aristóteles [Drittes Kapitel: Platon und Aristoteles] / A. Platón [A. Philosophie des Platon]

Tabla de contenidos

Vorlesungen im Atrium Philosophicum §12

Ein anderer historischer Umstand, der der Vielseitigkeit anzugehören scheint, ist allerdings dieser, daß von Alten und Neueren viel darüber gesprochen worden, Platon habe von Sokrates, von diesem und jenem Sophisten, vorzüglich aber von den Schriften der Pythagoreer in seinen Dialogen aufgenommen, – er habe offenbar viele ältere Philosophien vorgetragen, wobei Pythagoreische und Heraklitische Philosopheme und eleatische Weise der Behandlung vornehmlich sehr hervortritt, so daß diesen zum Teil die ganze Materie der Abhandlung und nur die äußere Form dem Platon angehöre, es also nötig wäre, dabei deswegen zu unterscheiden, was ihm eigentümlich angehöre oder nicht, oder ob jene Ingredienzien miteinander übereinstimmen. In dieser [22] Rücksicht aber ist zu bemerken, daß, indem das Wesen der Philosophie dasselbe ist, jeder folgende Philosoph die vorhergehenden Philosophien in die seinige aufnehmen wird und muß, – daß ihm das eigentümlich angehört, wie er sie weiter fortgebildet. Die Philosophie ist nicht so etwas Einzelnes als ein Kunstwerk, und selbst an diesem ist es die Geschicklichkeit der Kunst, die der Künstler von anderen empfangen wieder aufnimmt und ausübt. Die Erfindung des Künstlers ist der Gedanke seines Ganzen und die verständige Anwendung der vorgefundenen und bereiteten Mittel; dieser unmittelbaren Einfälle und eigentümlichen Erfindungen können unendlich viele sein. Aber die Philosophie hat zum Grunde einen Gedanken, ein Wesen, und an die Stelle der früheren wahren Erkenntnis desselben kann nichts anderes gesetzt werden, – sie muß in den Späteren ebenso notwendig vorkommen. Ich habe schon bemerkt, daß Platons Dialoge nicht so anzusehen sind, daß es ihm darum zu tun gewesen ist, verschiedene Philosophien geltend zu machen, noch daß Platons Philosophie eine eklektische Philosophie sei, die aus ihnen entstehe; sie bildet vielmehr den Knoten, in dem diese abstrakten einseitigen Prinzipien jetzt auf konkrete Weise wahrhaft vereinigt sind. In der allgemeinen Vorstellung der Geschichte der Philosophie sahen wir schon, daß solche Knotenpunkte in der Linie des Fortganges der philosophischen Ausbildung eintreten müssen, in denen das Wahre konkret ist. Das Konkrete ist die Einheit von unterschiedenen Bestimmungen, Prinzipien; diese, um ausgebildet zu werden, um bestimmt vor das Bewußtsein zu kommen, müssen zuerst für sich aufgestellt, ausgebildet werden. Da durch erhalten sie dann allerdings die Gestalt der Einseitigkeit gegen das folgende Höhere; dies vernichtet sie aber nicht, läßt sie auch nicht liegen, sondern nimmt sie auf als Momente seines höheren und tieferen Prinzips. In der Platonischen Philosophie sehen wir so vielerlei Philosopheme aus früherer Zeit, aber aufgenommen in seinem Prinzip und darin vereinigt. Dies Verhältnis ist, daß Platonische [23] Philosophie sich als eine Totalität der Idee beweist; die seinige, als Resultat, befaßt die Prinzipien der anderen in sich. Häufig hat Platon nichts anderes getan, als die Philosophien Älterer exponiert, und seiner ihm eigentümlichen Darstellung gehört nur dies an, sie erweitert zu haben. Sein Timaios ist nach allen Zeugnissen Erweiterung einer Pythagoreischen Schrift, die wir auch noch haben; überscharfsinnige Leute sagen, diese sei erst aus Platon gemacht. Seine Erweiterung ist auch bei Parmenides so, daß sein Prinzip in seiner Einseitigkeit aufgehoben ist.

Praelēctiōnēs in Ātriō Philosophicō §12

Esta circunstancia histórica, que parece formar parte también de la multiplicidad de aspectos de Platón, ha hecho, evidentemente, que muchos autores antiguos y modernos sostengan, con gran insistencia, la tesis de que Platón sólo pretendió exponer históricamente la doctrina y el modo de ser de Sócrates, aunque en sus diálogos se recoja también mucho de tales o cuales sofistas y también, manifiestamente, una parte considerable de la filosofía antigua, principalmente de la de Pitágoras, Heráclito y los eléatas, destacándose notablemente, en lo que a esta parte se refiere, el modo eleático de tratar los problemas; según quienes así piensan, toda la materia expuesta pertenece, muchas veces, a los filósofos de que se trata, limitándose Platón a poner de su cosecha la forma de exponerla, lo que hace que sea necesario, siempre según este punto de vista, entrar a distinguir lo que pertenece a Platón de lo que éste ha tomado de otros y si existe o no una unidad armónica entre aquellos ingredientes. Otra observación hay que hacer a este propósito, y es que, siendo la misma la esencia de la filosofía, cada filósofo que viene detrás incorporará necesariamente a la suya las filosofías precedentes, de tal modo que sólo podrá considerarse como obra propia y peculiar suya el modo como las lleva adelante y las desarrolla. La filosofía no es, pues, algo individual, como una obra de arte; y tampoco de ésta puede decirse que lo sea nunca en absoluto, pues también el artista recibe de otros y desarrolla por cuenta propia, al ejercerlas, las aptitudes artísticas. La invención del artista, su inspiración, es el pensamiento de su todo y la inteligente aplicación de los medios con que se encuentra, ya preparados; los motivos directos de inspiración y las verdaderas invenciones pueden ser infinitos. Pero la filosofía descansa sobre un pensamiento, sobre una esencia, sin que sea posible sustituir por otro el verdadero conocimiento anterior de ella, el cual tiene que surgir con la misma necesidad en los filósofos posteriores. Por eso hemos dicho ya, en otra parte,1Refiere a las primera páginas, que sirven de introducción, a la Primera parte («La Filosofía Griega»), Sección primera («Primer período: de Tales a Aristóteles») de estas Lecciones. que los diálogos de Platón no deben ser considerados como si en ellos se tratara de hacer valer diversas filosofías, como si la filosofía platónica fuese una filosofía ecléctica, formada por todas las anteriores. Esta filosofía constituye más bien el nodo en el que se unen verdaderamente, en forma concreta, todos estos principios abstractos y unilaterales. Al describir la noción general de la historia de la filosofía2Refiere a la Introducción a la Historia de la Filosofía, en especial su Parte A («Concepto de la historia de la filosofía»), Apartado 3 («Resultados para el concepto de historia de la filosofía») de estas Lecciones. hemos dicho ya que en la trayectoria del desarrollo progresivo del pensamiento filosófico tienen que darse, necesariamente, ciertos puntos nodulares en los que lo verdadero aparezca de un modo concreto. Lo concreto es la unidad de distintos principios y determinaciones; estos principios y determinaciones, para desarrollarse, para que se revelen a la conciencia de un modo claro y preciso, es necesario que empiecen estableciéndose para sí. Claro está que, con ello, adquieren la forma de algo unilateral en comparación con los principios y determinaciones superiores que después vendrán; pero esto no los destruye ni los deja a un lado, sino que los incorpora y se los asimila como momentos de su principio superior. En la filosofía platónica nos encontramos, así, con muchos filosofemas procedentes de una época anterior, pero asimilados al principio platónico, más profundo que ellos, y unificados en él. Desde este punto de vista, la filosofía platónica se revela como una totalidad de la idea, es decir, como un resultado, que encuadra y armonizá los principios de las otras filosofías. Frecuentemente, Platón se limita a exponer las filosofías de los pensadores antiguos, y lo peculiar de su propia exposición consiste, exclusivamente, en ampliar y desarrollar aquellas filosofías. Su Timeo es, según todos los testimonios que poseemos,3Scholia in Timaeum, p. 423 ss. (ed. Bekker: Commentar. Crit. In Plat. Tim., t. II). la ampliación y el desarrollo de una obra de Pitágoras, que ha llegado a nosotros; también el Parménides es una ampliación y un desarrollo de doctrinas anteriores, de tal modo que su principio queda superado, así, en su propia unilateralidad.

Perge ad initium paginae huius

Lectures at the Atrium Philosophicum §12

Another historical circumstance which seems to be part of the diversity is that it has been said a lot by ancients and moderns about the fact that Plato incorporated Socrates, this or that sophist, but especially the writings of the Pythagoreans in his dialogues – he evidently presented many older philosophies, in which Pythagorean and Heraclitean philosophemes and the Eleatic method of treatment are particularly prominent, so that in part the whole subject matter of the treatise and only the external form belong to Plato, and it is therefore necessary to distinguish what belongs to him or not, or whether those ingredients agree with one another. This further observation we must, however, make, that since Philosophy in its ultimate essence is one and the same, every succeeding philosopher will and must take up into his own, all philosophies that went before, and what falls specially to him is their further development. Philosophy is not a thing apart, like a work of art; though even in a work of art it is the skill which the artist learns from others that he puts into practice. What is original in the artist is his conception as a whole, and the intelligent use of the means already at his command; there may occur to him in working an endless variety of ideas and discoveries of his own. But philosophy has at its foundation an idea, an essence, and nothing else can be put in place of the earlier true knowledge of it – it must just as necessarily appear in the later ones. Therefore, as I have already observed,4He is referring to the first pages of, a brief introduction to, the First Part («Greek Philosophy»), Section One («First Period, from Thales to Aristotle») of the present Lectures. Plato’s Dialogues are not to be considered as if their aim were to put forward a variety of philosophies, nor as if Plato’s were an eclectic philosophy derived from them; it forms rather the node in which these abstract and one-sided principles have become truly united in a concrete fashion. In giving a general idea of the history of Philosophy, we have already seen5He is referring to the Introduction to the History of Philosophy, specifically the Part A («Notion of the History of Philosophy»), Section 3 («Results obtained with respect to the notion of the History of Philosophy») of the resent Lectures. that such nodes, in which the true is concrete, must occur in the onward course of philosophical development. The concrete is the unity of diverse determinations and principles; these, in order to be perfected, in order to come definitely before the consciousness, must first of all be presented separately. Thereby they of course acquire an aspect of one-sidedness in comparison with the higher principle which follows: this, nevertheless, does not annihilate them, nor even leave them where they were, but takes them up into itself as moments. Thus in Plato’s philosophy we see all manner of philosophic teaching from earlier times absorbed into a deeper principle, and therein united. This relationship is that Platonic philosophy proves itself to be a totality of the idea; his, as a result, includes the principles of the others within itself. Frequently Plato does nothing more than explain the doctrines of earlier philosophers; and the only particular feature in his representation of them is that their scope is extended. His Timaeus is, according to all evidence,6cf. Scholia in Timaeum, p. 423 ss. (ed. Bekker: Commentar. Crit. In Plat. Tim., t. II. an expansion of a Pythagorean text, which we still have; overly astute people say that this was first made out of Plato. In like manner, his amplification is also in Parmenides such that its principle is freed from its one-sidedness.