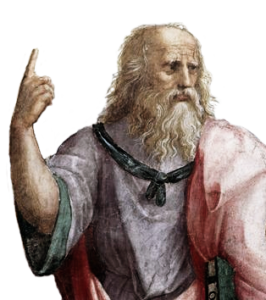

Hegel über Platon 011

Parte de:

Lecciones de Historia de la Filosofía [Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie] / Primera parte: La Filosofía Griega [Erster Teil: Griechische Philosophie] / Sección Primera: de Tales a Aristóteles [Erster Abschnitt. Von Thales bis Aristoteles] / Capítulo 3: Platón y Aristóteles [Drittes Kapitel: Platon und Aristoteles] / A. Platón [A. Philosophie des Platon]

Tabla de contenidos

Vorlesungen im Atrium Philosophicum §11

Es kann unter die Schwierigkeiten, die eigentliche Spekulation Platons zu erfassen, nicht die historische Seite gerechnet werden, daß Platon in seinen Dialogen nicht in eigener Person spricht, sondern Sokrates und viele andere Personen redend einführt, von denen man nicht immer wisse, welche eigentlich das vortrage, was Platons Meinung sei. Es könnte den Schein haben, als ob er nur geschichtlich die Weise und Lehre des Sokrates besonders vorgestellt habe. Bei sokratischen Dialogen, wie sie Cicero gibt, da kann man eher die Personen herausfinden; aber bei Cicero ist kein gründliches Interesse vorhanden. Bei Platon kann jedoch von dieser Zweideutigkeit eigentlich nicht die Rede sein, diese äußerliche Schwierigkeit ist nur scheinbar; aus seinen Dialogen geht seine Philosophie ganz deutlich hervor. Denn die Platonischen Dialoge sind nicht so beschaffen wie die Unterredung mehrerer, die aus vielen Monologen besteht, wovon der eine dies, der andere jenes meint und bei seiner Meinung bleibt. Sondern die Verschiedenheit der Meinungen, die vorkommt, ist untersucht; es ergibt ein Resultat als das Wahre; oder die ganze Bewegung des Erkennens, wenn das Resultat negativ ist, ist es, die Platon angehört.

Praelēctiōnēs in Ātriō Philosophicō §11

Entre las dificultades con que se tropieza para captar la verdadera especulación platónica no puede incluirse, en tercer lugar, el lado externo de que Platón, en sus diálogos, no habla en propia persona, sino que introduce en ellos, como interlocutores, a Sócrates y otros muchos personajes, sin que sea posible saber siempre cuál de ellos expone, en realidad, los puntos de vista de Platón. En los diálogos socráticos como los compuestos por Cicerón es más bien fácil identificar los personajes; lo que ocurre es que Cicerón no obra movido por un interés profundo. Pero en Platón no cabe hablar, en rigor, de este equívoco; y esta dificultad a que nos referimos es puramente aparente. De los diálogos de Platón se trasluce claramente la filosofía que los inspira, pues no están compuestos como coloquios formados, en realidad, por varios monólogos en que el uno sostenga una cosa y el otro otra, aferrándose cada cual a sus propias opiniones. En estos diálogos no ocurre tal cosa, sino que se investiga la disparidad de opiniones que en ellos se manifiesta y se llega siempre a un resultado como el verdadero; y, cuando el resultado a que se llega es negativo, hay toda una trayectoria de conocimiento que es obra del propio Platón. No es, pues, necesario detenerse a investigar qué es lo que, en la exposición de cada diálogo, pertenece a Platón y lo que es obra de Sócrates.

Perge ad initium paginae huius

Lectures at the Atrium Philosophicum §11

The difficulties in understanding Plato’s actual speculations cannot be counted among the historical side of the fact that Plato does not speak in person in his dialogues, but introduces Socrates and many other people speaking, of whom one does not always know which one actually expresses what Plato’s opinion is. It might seem as if he only presented the manner and teaching of Socrates in historical terms. In Socratic dialogues such as those given by Cicero, one can more easily identify the people; but in Cicero’s case there is no thorough interest. In Plato, however, there can really be no question of this ambiguity; this external difficulty is only apparent; his philosophy is quite clear from his dialogues. For the Platonic dialogues are not like the conversation of several people, which consists of many monologues, where one thinks this, the other that, and sticks to his opinion. Rather, the diversity of opinions that occurs is examined; it produces a result that is the true one; or the whole movement of knowing, if the result is negative, is what Plato belongs to. There is, therefore, no need to inquire further as to what belongs to Socrates in the Dialogues, and what belongs to Plato.