Hegel über Platon 007

Parte de:

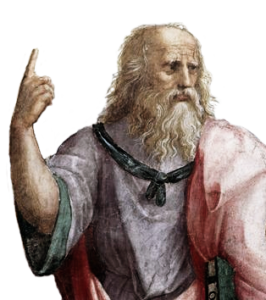

Lecciones de Historia de la Filosofía [Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie] / Primera parte: La Filosofía Griega [Erster Teil: Griechische Philosophie] / Sección Primera: de Tales a Aristóteles [Erster Abschnitt. Von Thales bis Aristoteles] / Capítulo 3: Platón y Aristóteles [Drittes Kapitel: Platon und Aristoteles] / A. Platón [A. Philosophie des Platon]

Tabla de contenidos

Vorlesungen im Atrium Philosophicum §7

Platons Hoffnungen scheiterten. Es war eine Verirrung Platons, durch Dionysios die Staatsverfassungen den Forderungen seiner philosophischen Idee anpassen zu wollen. Später schlug Platon es sogar anderen Staaten, die sich ausdrücklich an ihn wandten und ihn darum ersuchten, unter anderen den Bewohnern von Kyrene und den Arkadiern, ab, ihr Gesetzgeber zu werden. Es war eine Zeit, wo [18] viele griechische Staaten nicht mehr zurechtzukommen wußten mit ihren Verfassungen, ohne etwas Neues finden zu können. Jetzt, in den letzten dreißig Jahren, hat man viele Verfassungen gemacht, und jedem Menschen, der sich viel damit beschäftigt hat, wird es leicht sein, eine solche zu machen. Aber das Theoretische reicht bei einer Verfassung nicht hin, es sind nicht Individuen, die sie machen; es ist ein Göttliches, Geistiges, was sich durch die Geschichte macht. Es ist so stark, daß der Gedanke eines Individuums gegen diese Macht des Weltgeistes nichts bedeutet; und wenn diese Gedanken etwas bedeuten, realisiert werden können, so sind sie nichts anderes als das Produkt dieser Macht des allgemeinen Geistes. Der Einfall, daß Platon Gesetzgeber werden sollte, war dieser Zeit nicht angemessen; Solon, Lykurg waren es, aber in der Zeit Platons war dies nicht mehr zu machen. Platon lehnte ein weiteres Einlassen in den Wunsch jener Staaten ab, weil sie nicht in die erste Bedingung einwilligten, welche er ihnen machte, und diese war die Aufhebung alles Privateigentums. Dies Prinzip werden wir später noch betrachten bei seiner praktischen Philosophie.

Praelēctiōnēs in Ātriō Philosophicō §7

Así fracasaron las esperanzas de Platón; y no cabe duda de que el gran pensador se equivocó al creer que podría adaptar, gracias a Dionisio, la organización práctica del Estado a sus postulados filosóficos. Aleccionado por esta experiencia, Platón rechazó las invitaciones de otros Estados, entre otras las de los habitantes de Cirene y Arcadia, que se dirigieron a él pidiéndole expresamente que fuese su legislador. Era una época en que muchos Estados griegos comprendían que no podían salir adelante con las constituciones en ellos vigentes, pero sin acertar a descubrir por su cuenta nada nuevo.1Platón, Cartas, VII, p. 326 (p. 431). En nuestro tiempo, en estos últimos treinta años,2Del curso de lecciones de 1825 [M.]., se han redactado también muchas constituciones nuevas; es ésta una tarea fácil de realizar para quien se halle habituado a esta clase de trabajos. Sin embargo, el talento teórico no basta para redactar una constitución viable, pues los que las hacen no son los individuos, sino algo espiritual, algo divino, que se realiza a través de la historia. Es algo tan fuerte, que el pensamiento de un individuo no significa nada frente a esta potencia del espíritu universal. Y, suponiendo que tales pensamientos signifiquen algo, es decir, que puedan ser realizados, no son sino el producto de esta fuerza del espíritu general. La idea de que Platón se erigiese en legislador no era una idea adecuada a aquel tiempo; Solón y Licurgo lo habían sido, pero en la época de Platón esta idea era ya irrealizable. Platón se negó a acceder a los deseos de aquellos Estados que le solicitaban como legislador porque no aceptaron la primera condición que para ello les puso, la cual no fue otra que la abolición de la propiedad privada,3Diógenes Laercio, III, 23 (Menag. ad. h. l.); Eliano, Var. Histor. II, 42; Plutarco, Ad principem ineruditum, init. p. 779, ed. Xyl. principio que tendremos ocasión de examinar más adelante, cuando estudiemos su filosofía práctica.

Perge ad initium paginae huius

Lectures at the Atrium Philosophicum §7

Plato’s hopes foundered, for through Dionysius he had not succeeded in putting into effect the Idea of the state. Other states that turned to him for that express purpose, such as Cyrene, invited him to become their lawgiver, but Plato declined the offers X16X. (At that time several Greek states were no longer satisfied with their constitutions, but they did not find a good type of constitution anywhere else either X17X.) We have seen many constitutions drawn up in the past thirty years, and anyone who takes the trouble to do it will find it easy to devise one. An a priori constitution, however, is far from adequate; and individuals are not the ones who make the constitution. The constitution is something divine, something higher; it is historically necessary, irresistible, and strong, so that the thoughts of one individual signify nothing over against the power of the world spirit and the strength of the national spirit; if those thoughts do have some significance, if they can be realized, then they are nothing other than the product of this power of the universal spirit. It was a false notion for those times that Plato should be the lawgiver in the state. Yes, Solon and Lycurgus could be lawgivers X18X; but in Plato’s day this was no longer possible. Plato refused to do it because they did not consent to the first condition he set for them, which was the abolition of all private property, because there could be no such thing in a genuine state. We will deal with this principle later on, in his practical philosophy X19X. The Arcadians turned to Plato in similar fashion, but he rejected their request too X20X.

Some clarifications

X16X

See Diogenes Laertius (Lives 3.23; Hicks, i. 296-9), who mentions Arcadia and Thebes. Hegel’s mention of Cyrene may derive from Plutarch. See Plutarch’s Ad principem ineruditum 1, which states that the invitation came from Cyrene, not from Arcadia or Thebes, and that Plato refused because the Cyrenaeans were so prosperous that it was difficult to make laws for them, See Plutarch’s Moralia, vol. x, trans. H. N, Fowler (Loeb Classical Library; Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1936), 52-3.

X17X

This may refer to Plato’s own judgment that all existing states were badly governed (Seventh Epistle 326a-b; Bury, pp. 482-3).

X18X

See I.A.1 on this Lectures on the History of Philosophy (“The Seven Sages and the Milenians: Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes”) for the account of the lawgiving activities of the seven sages.

X19X

This point about the refusal of his views on property goes beyond Hegel’s main sources and may come from Aelian (c. AD 170-235), Variae historiae 2.42, which connects equality of possessions (τὸ ἶσον ἔχειν) with political equality (ἰσονομία), but without mentioning abolition of private property. Reference to Aelian at 3.23 appears in various editions of Diogenes Laertius. See also I.C.2 on this Lectures on the History of Philosophy (“Aristotle”).

X20X

See note X16X just above.