Hegel über Platon 004

Parte de:

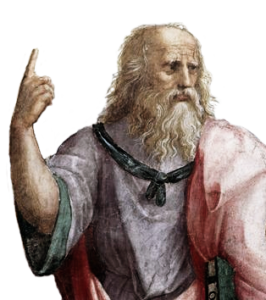

Lecciones de Historia de la Filosofía [Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie] / Primera parte: La Filosofía Griega [Erster Teil: Griechische Philosophie] / Sección Primera: de Tales a Aristóteles [Erster Abschnitt. Von Thales bis Aristoteles] / Capítulo 3: Platón y Aristóteles [Drittes Kapitel: Platon und Aristoteles] / A. Platón [A. Philosophie des Platon]

Tabla de contenidos

Vorlesungen im Atrium Philosophicum §4

Ein Gedanke, der sich auch bei Shakespeare in Romeo und Julia findet. Er dachte übrigens in seiner Jugend nicht anders, als sich den Staatsgeschäften zu widmen. Er wurde von seinem Vater bald zu Sokrates gebracht. »Es wird erzählt, daß Sokrates die Nacht vorher geträumt habe, er habe einen jungen Schwan auf seinen Knien sitzen, dessen Flügel schnell gewachsen und der jetzt aufgeflogen sei« (zum Himmel) »mit den lieblichsten Gesängen.« Überhaupt erwähnen die Alten vieler solcher Züge, die die hohe Verehrung und Liebe beurkunden, die seiner stillen Größe, seiner Erhabenheit in der höchsten Einfachheit und Lieblichkeit von seinen Zeitgenossen und den Späteren zuteil geworden und ihm den Namen des Göttlichen gegeben hat. Sokrates’ Umgang und Weisheit konnte Platon nicht genügen. Er beschäftigte sich noch mit den älteren Philosophen, vornehmlich dem Heraklit. Aristoteles gibt an, daß er, schon ehe er zu Sokrates gekommen, mit Kratylos umgegangen und in die Heraklitische Lehre eingeweiht [worden sei]. Er studierte auch die Eleaten und insbesondere die Pythagoreer und hatte Umgang mit den berühmtesten Sophisten. [14] Nachdem er sich so in die Philosophie vertieft hatte, verlor er das Interesse an Staatsangelegenheiten, entsagte denselben gänzlich und widmete sich ganz den Wissenschaften. Seine Pflicht des Kriegsdienstes als Athenienser erfüllte er wie Sokrates; er soll drei Feldzüge mitgemacht haben.

Praelēctiōnēs in Ātriō Philosophicō §4

Por lo demás, en su juventud Platón no pensaba en otra cosa que en dedicarse a los asuntos del Estado. Pero a los veinte años fue llevado por su padre a Sócrates y se mantuvo por espacio de ocho en contacto con él. Se cuenta que Sócrates, la noche antes, había tenido un sueño en el que un joven cisne se posaba sobre sus rodillas y que luego, habiéndole crecido rápidamente las alas, volaba hacia el cielo, entre maravillosos cantos. Los antiguos relatan muchos rasgos de éstos, en los que resaltan el amor y la veneración que la serena grandeza de Platón, la suprema sencillez y el encanto de su persona, llevados hasta el grado de lo sublime, infundían en sus contemporáneos y en las generaciones posteriores y que le valieron el nombre de Platón «el divino». El trato con Sócrates y la sabiduría de este maestro no podían bastarle a Platón. Estudió, además, a los filósofos antiguos, principalmente a Heráclito. Aristóteles (Metaf. I, 6) indica que, ya antes de conocer a Sócrates, había sostenido trato con Cratilo y se había iniciado en la doctrina heracliteana. Estudió también a los eléatas y, especialmente, a los pitagóricos y conoció y trató a los más famosos sofistas. Después de ahondar en el estudio de la filosofía, perdió el interés por la poesía y los negocios públicos y los abandonó totalmente para dedicarse por entero a las ciencias. Cumplió con sus deberes militares como ateniense, al igual que Sócrates; se dice que tomó parte en tres campañas.1Platón, Cartas, VII, pp. 324-326 (pp. 428-431); Diógenes Laercio, III, 5 s., 8.

Perge ad initium paginae huius

Lectures at the Atrium Philosophicum §4

Later he wished to devote himself to public affairs X3X. Early on his father brought him to Socrates. The story goes that, on the night before, Socrates had dreamed that he held a young swan on his knees and that it quickly grew wings and soared aloft, singing sweetly X4X. There are many such indications [in ancient authors] of the love and reverence felt for Plato. He was even called ‘the divine Plato’. His contemporaries already recognized the quiet greatness and sublimity [manifest] in his utmost simplicity and sweetness X5X. The company of Socrates by itself did not suffice for Plato. Previously he had occupied himself with the teaching of Heraclitus. He associated also with famous Sophists, and studied the Eleatics and the Pythagoreans X6X. After he had immersed himself thus in philosophy he gave up participation in public affairs and devoted himself wholly to the [philosophical] sciences, while still fulfilling his civic obligations. He had to go on military campaigns, and he went on three of them X7X.

Some clarifications

X3X

This is probably a reference to Plato’s Seventh Epistle (324b-5d), in which he reflects on the rule of the Thirty and the fate of Socrates; see Plato, Timaeus, Critias, Cleitophon, Menexenus, Epistles, trans. R. G. Bury (Loeb Classical Library; Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1929), 476-81.

X4X

Diogenes Laertius, in recounting this story (Lives 3.5; Hicks, i, 280-1), does not say that Ariston, Plato’s father, brought him to Socrates; that statement occurs in Jacob Brucker, Historia critica philosophiae, 4 vols. (Leipzig, 1742-4), i. 631.

X5X

Diogenes Laertius presents several epigrams about Plato that verge on attributing ‘divinity’ to him (Lives 3.43-5; Hicks, i. 314-17), as well as references to Apollo’s role in Plato’s conception and birth (3.2; Hicks, i. 276-9). See also n. 21 just below.

X6X

In saying that Socrates did not suffice for Plato, Hegel may be influenced by Aristotle’s remark that Socrates dealt with ethics but not with nature as a whole (Metaphysics 987b. 1-2); see The Complete Works of Aristotle, ed. Jonathan Barnes, 2 vols. (Princeton, 1984), ii, 1361. In a preceding passage (987a.32-5) Aristotle had noted Plato’s early interest in the philosophy of Heraclitus (Barnes, ii. 1561). Diogenes Laertius, however, places Plato’s interest in Heraclitus after the death of Socrates (Lives 3.6; Hicks, i, 280-1), and says that he mixed together the doctrines of Heraclitus, the Pythagoreans, and Socrates, concerning sensible things, intelligible objects, and political masters respectively (3.8; Hicks, i. 282-5), Plato’s concern with Eleatic philosophy is evident in his dialogue Parmenides, and his familiarity with famous Sophists is clear in the titles and content of the Hippias, the Gorgias, the Protagoras, and in the speeches of characters in the Symposium. On his study of Pythagorean philosophy, see n. 10 just below.

X7X

Plato’s Seventh Epistle, Hegel’s likely source, attributes Plato’s turn away from participation in Athenian civic affairs to his disenchantment with the tyranny of the Thirty and the subsequent condemnation of Socrates—events that nevertheless heightened his desire to unite philosophy with governance (324d-6b; Bury, pp. 478-83). Diogenes Laertius, citing Aristoxenus, names the three military campaigns in which Plato served (Lives 3.8; Hicks, i, 282-3).