Ethica Nicomachea L-II 001

Ēthica Nicōmachea sīve Dē mōribus ad Nicōmachum (Aristotelēs)

Ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια (Ἀριστοτέλης)

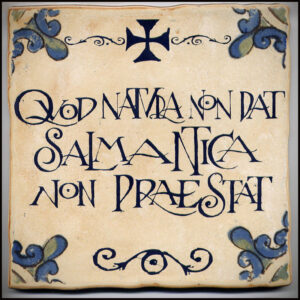

OFFICĪNA PHILOSOPHŌRVM ***

(1103a)

Parte de:

Ética Nicomáquea / Libro II / [1. La virtud ética, un modo de ser de la recta acción]

Tabla de contenidos

Ēthica Nicōmachea L-II 001

[1103a] [14] Διττῆς δὴ τῆς ἀρετῆς οὔσης, τῆς μὲν διανοητικῆς τῆς [15] δὲ ἠθικῆς, ἡ μὲν διανοητικὴ τὸ πλεῖον ἐκ διδασκαλίας ἔχει καὶ τὴν γένεσιν καὶ τὴν αὔξησιν, διόπερ ἐμπειρίας δεῖται καὶ χρόνου, ἡ δ᾽ ἠθικὴ ἐξ ἔθους περιγίνεται, ὅθεν καὶ τοὔνομα ἔσχηκε μικρὸν παρεκκλῖνον ἀπὸ τοῦ ἔθους. ἐξ οὗ καὶ δῆλον ὅτι οὐδεμία τῶν ἠθικῶν ἀρετῶν φύσει ἡμῖν ἐγγίνεται· οὐθὲν [20] γὰρ τῶν φύσει ὄντων ἄλλως ἐθίζεται, οἷον ὁ λίθος φύσει κάτω φερόμενος οὐκ ἂν ἐθισθείη ἄνω φέρεσθαι, οὐδ᾽ ἂν μυριάκις αὐτὸν ἐθίζῃ τις ἄνω ῥιπτῶν, οὐδὲ τὸ πῦρ κάτω, οὐδ᾽ ἄλλο οὐδὲν τῶν ἄλλως πεφυκότων ἄλλως ἂν ἐθισθείη. οὔτ᾽ ἄρα φύσει οὔτε παρὰ φύσιν ἐγγίνονται αἱ ἀρεταί, ἀλλὰ [25] πεφυκόσι μὲν ἡμῖν δέξασθαι αὐτάς, τελειουμένοις δὲ διὰ τοῦ ἔθους.

Perge ad initium paginae huius

Ética Nicomáquea L-II 001

NATURALEZA DE LA VIRTUD ÉTICA

[1. La virtud ética, un modo de ser de la recta acción]

[1103a] Existen, pues, dos clases de virtud, la dianoética y la ética. La dianoética se origina y crece principalmente por la enseñanza, y por ello requiere experiencia y tiempo; la ética, en cambio, procede de la costumbre, como lo indica el nombre que varía ligeramente del de «costumbre».1Así el término ἠθικός (ēthikós) procedería de ἦθος (êthos) «carácter», que, a su vez, Aristóteles relación con ἔθος (éthos) «hábito, costumbre». También PLATÓN (Leyes VII 792e) dice: «Toda disposición de carácter procede de la costumbre» («πᾶν ἦθος διὰ ἔθος»). De este hecho resulta claro que ninguna de las virtudes éticas se produce en nosotros por naturaleza, puesto que ninguna cosa que existe por naturaleza se modifica por costumbre. Así la piedra que se mueve por naturaleza hacia abajo, no podría ser acostumbrada a moverse hacia arriba, aunque se intentara acostumbrarla lanzándola hacia arriba innumerables veces; ni el fuego, hacia abajo; ni ninguna otra cosa, de cierta naturaleza, podría acostumbrarse a ser de otra manera. De ahí que las virtudes no se produzcan ni por naturaleza ni contra naturaleza, sino que nuestro natural pueda recibirlas y perfeccionarlas mediante la costumbre.2La costumbre es primordial en la adquisición de la virtud, pero la naturaleza desempeña también su papel en la capacidad natural para adquirir y perfeccionar las virtudes o vicios.

Nicomachean Ethics L-II 001

[1103a] Virtue being, as we have seen, of two kinds, intellectual and moral, intellectual virtue is for the most part both produced and increased by instruction, and therefore requires experience and time; whereas moral or ethical virtue is the product of habit [ethos], and has indeed derived its name, with a slight variation of form, from that word.3It is probable that ἔθος, ‘habit’ and ἦθος, «character» (whence «ethical,» moral) are kindred words. And therefore it is clear that none of the moral virtues formed is engendered in us by nature, for no natural property can be altered by habit. For instance, it is the nature of a stone to move downwards, and it cannot be trained to move upwards, even though you should try to train it to do so by throwing it up into the air ten thousand times; nor can fire be trained to move downwards, nor can anything else that naturally behaves in one way be trained into a habit of behaving in another way. The virtues4ἀρετή is here as often in this and the following Books employed in the limited sense of ‘moral excellence’ or ‘goodness of character,’ i.e. virtue in the ordinary sense of the term. therefore are engendered in us neither by nature nor yet in violation of nature; nature gives us the capacity to receive them, and this capacity is brought to maturity by habit.

Ad Nicomachum filium de Moribus L-II 001

[1103a] Sed cum duo sint virtūtum genera, alterum eārum quās in ratiōne esse dīcimus, alterum eārum quās mōrālēs & voluntāriās: ratiōnis quidem magna ex parte ā doctrīnā ortum accessiōnemque habent. Itaque & exercitātiōnis indigent & temporis ἡ δ᾽ ἠθικὴ, id est mōrālis & voluntāria virtūs, ἐξ ἔθους id est mōre, ā quō nōmen dūxit, quod paulum ἀπὸ τοῦ ἔθους dēflexit, omnīnō comparātur. Ex quō perspicuum est, nūllam omnīnō mōrālium virtūtum ingenerārī nōbīs nātūra. Nihil enim quod īnsitum & innātum est, aliter atque est assuēscit. Ut lapis quī suapte sponte deorsum fertur, nōnquam in sublīme ferrī assuēscat, nē sī mīliēs quidem eum quis sūrsum ut cōnsuefaciat, ēmittat. Eōdemque modō nec ignis deorsum, nec aliud quicquam aliter atque ipsīus nātūrā ferat, potest assuēscere. Nōn igitur ā nātūrā, nēque contrā nātūram in nōbīs īnsunt virtūtēs: sed nātī factīque sumus ad eās & percipiendās nātūrā, & efficiendās consuetudine.

Perge ad initium paginae huius

Conversaciones en el Atrium

EN CONSTRVCCION

EN CONSTRVCCION

Perge ad initium paginae huius

OFFICĪNA PHILOSOPHŌRVM ***