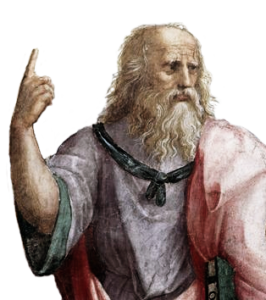

Hegel über Platon 013

Parte de:

Lecciones de Historia de la Filosofía [Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie] / Primera parte: La Filosofía Griega [Erster Teil: Griechische Philosophie] / Sección Primera: de Tales a Aristóteles [Erster Abschnitt. Von Thales bis Aristoteles] / Capítulo 3: Platón y Aristóteles [Drittes Kapitel: Platon und Aristoteles] / A. Platón [A. Philosophie des Platon]

Tabla de contenidos

Vorlesungen im Atrium Philosophicum §13

Die Platonischen Werke sind bekanntlich Dialoge, und es ist zuerst von der Form zu reden, in der Platon seine Ideen vorgetragen hat, sie zu charakterisieren; andernteils ist sie aber von dem, was Philosophie als solche bei ihm ist, abzuziehen. Die Form der Platonischen Philosophie ist die dialogische. Die Schönheit dieser Form ist vornehmlich anziehend dabei. Man muß nicht dafür halten, daß es die beste Form der philosophischen Darstellung sei. Sie ist Eigentümlichkeit Platons und als Kunstwerk allerdings wert zu achten. Häufig setzt man die Vollkommenheit in dieser Form.

Zur äußeren Form gehört zunächst die Szenerie und das Dramatische; das Anmutige ist, daß Szene, individuelle Veranlassung da ist der Dialoge. Platon macht ihnen eine Umgebung von Wirklichkeit des Lokals und dann der Personen, der Veranlassung, welche sie zusammengeführt, die für sich schon sehr lieblich, offen und heiter ist. Wir werden zu einem Orte, zum Platanenbaum im Phaidros (229), zum klaren Wasser des Ilyssos, durch den Sokrates und Phaidros hindurchgehen, zu den Hallen der Gymnasien, zur Akademie, zu einem Gastmahle geführt. Aber noch mehr ist diese Erfindung äußerlicher, spezieller, zufälliger insbesondere, Veranlassungen partikularisiert. Es sind lauter andere Personen, denen Platon seine Gedanken in den Mund legt, so daß er selbst nie namentlich auftritt und damit alles Thetische, Behauptende, Dogmatisierende völlig abwälzt und wir ebensowenig ein – ihn als – Subjekt [24] auftreten sehen als in der Geschichte des Thukydides oder im Homer. Xenophon läßt teils sich selbst auftreten, teils gibt er überall das Absichtliche vor, die Lehrweise und das Leben durch Beispiele zu rechtfertigen. Bei Platon ist alles ganz objektiv und plastisch; es ist Kunst, es weit von sich zu entfernen, oft in die dritte, vierte Person hinauszuschieben (Phaidon). Sokrates ist Hauptperson, dann andere Personen; viele sind uns bekannte Sterne: Agathon, Zenon, Aristophanes. Was von dem in den Dialogen Dargestellten dem Sokrates oder dem Platon angehöre, bedarf keiner weiteren Untersuchung. Soviel ist gewiß, daß wir aus Platons Dialogen sein System vollkommen zu erkennen imstande sind.

Im Ton der Darstellung des persönlichen Verhaltens der Unterredungen herrscht die edelste (attische) Urbanität gebildeter Menschen. Feinheit des Betragens lernt man daraus. Man sieht den Weltmann, der sich zu benehmen weiß. Höflichkeit drückt nicht ganz Urbanität aus. Höflichkeit enthält etwas mehr, einen Überfluß, noch Bezeugungen von Achtung, von Vorzug, von Verpflichtungen, die man ausdrückt. Die Urbanität ist die wahrhafte Höflichkeit; diese liegt zugrunde. Urbanität bleibt aber dabei stehen, dem anderen die persönliche vollkommene Freiheit seiner Sinnesart, Meinungen zuzugestehen, – das Recht, sich zu äußern, einem jeden, mit dem man spricht, einzuräumen und in seiner Gegenäußerung, Widerspruch diesen Zug auszudrücken, – sein eigenes Sprechen für ein subjektives zu halten gegen das Äußern des anderen, weil es eine Unterredung ist, Personen als Personen auftreten, nicht der objektive Verstand oder Vernunft sich mit sich bespricht. (Vieles ist, was wir zur bloßen Ironie ziehen.) Bei aller Energie der Äußerung ist dies immer anerkannt, daß der andere auch verständige, denkende Person ist. Man muß nicht vom Dreifuß versichern, dem anderen über den Mund fahren. Diese Urbanität ist nicht Schonung, es ist größte Freimütigkeit; sie macht die Anmut der Dialoge Platons. [25]

Praelēctiōnēs in Ātriō Philosophicō §13

Después de eliminadas estas dos últimas dificultades, es necesario, para lograr la solución de la primera, caracterizar ante todo la forma en que Platón expone sus ideas; y, por otra parte, hay que descontar esa forma de lo que en Platón es la filosofía como tal. La forma de la filosofía platónica es, como sabemos, el dialogo. Indudablemente, esta forma reviste una belleza muy atractiva; sin embargo, sería falso sostener, como a veces se sostiene, que sea ésta la forma más perfecta y acabada de la exposición filosófica; es, desde luego, una peculiaridad de Platón, y no cabe duda de que se le debe dar toda la importancia que merece como obra de arte.

La forma externa incluye, en primer lugar, la escenografía y el elemento dramático. Platón sitúa sus diálogos en un ambiente de realidad, en lo tocante al medio en que se desenvuelven y a los personajes que en ellos intervienen, y toma siempre como punto de partida un motivo individual, que reúne a los personajes y da un carácter de verosimilitud muy agradable y abierto a sus coloquios. El autor nos sitúa, además, en un lugar concreto: el Fedro (p. 229 Steph., p. 6 Bekk.) se desarrolla a la sombra de un plátano junto a las claras aguas del Iliso, que Sócrates y Fedro cruzan; otros diálogos tienen por escenario los pórticos de los gimnasios, la Academia, la sala en que se celebra un banquete. Mediante el recurso de no intervenir nunca personalmente, poniendo siempre sus pensamientos en boca de otros personajes, Platón logra suprimir totalmente en sus diálogos lo que pudiera haber en ellos de tesis, de elemento dogmático. Tampoco aparece en los diálogos platónicos un sujeto encargado de narrar, como en la historia de Tucídides o en los poemas de Homero. Jenofonte aparece, a veces, en persona y, a veces, deja traslucir claramente su intención de justificar por medio de ejemplos la doctrina y la vida de Sócrates. En Platón, por el contrario, todo es absolutamente objetivo y plástico, y le vemos desplegar un gran arte para evitar todo lo que sea puramente expositivo, desplazándolo a veces, incluso, a la tercera o cuarta persona. El personaje principal, en estos diálogos, es Sócrates; entre los demás interlocutores aparecen muchas primeras figuras conocidas de nosotros, tales como Agatón, Zenón, Aristófanes, etc. Lo pertenezca a Sócrates o a Platón de lo representado en los diálogos pertenece a Sócrates o a Platón no requiere mayor investigación. Una cosa es segura: podemos reconocer plenamente su sistema en los diálogos de Platón.

En cuanto al tono que predomina en la actitud de los personajes que intervienen en el coloquio, es de la más noble urbanidad propia de gentes cultas; es una finura de conducta detrás de la cual se ve al hombre de mundo que sabe cómo conducirse. La cortesía no expresa enteramente lo que es la urbanidad, pues contiene algo más que ésta, un algo superfluo, ciertas manifestaciones o demostraciones de respeto, de sumisión, etc. La urbanidad es la verdadera cortesía y sirve de base a ésta. Uno de sus postulados consiste en reconocer a todo aquel con quien se habla una absoluta libertad personal para sentir y pensar como le parezca y el derecho de expresarse libremente, lo cual supone que, al contestar o contradecir los puntos de vista del interlocutor, se consideren las propias opiniones simplemente como la expresión de algo subjetivo; trátase, en efecto, de pláticas entre personas, y no de un monólogo de la razón objetiva. Por mucha que sea la energía que se ponga en las manifestaciones, no se pierde nunca de vista que también el otro es un sujeto pensante, cuyos puntos de vista son igualmente dignos de ser escuchados. Pero esta urbanidad no debe confundirse con el temor a herir susceptibilidades, sino que lleva consigo, por el contrario, una gran valentía y una gran franqueza, y es esto precisamente lo que constituye el encanto de los diálogos platónicos.

Perge ad initium paginae huius

Lectures at the Atrium Philosophicum §13

The Platonic works are, as is well known, dialogues, and we must first speak of the form in which Plato presented his ideas in order to characterize them; on the other hand, however, it must be deducted from what philosophy as such is for him. The form of Platonic philosophy is dialogical. The beauty of this form is particularly attractive. One must not consider it to be the best form of philosophical presentation. It is a peculiarity of Plato and certainly worthy of respect as a work of art. Perfection is often placed in this form.

The external form includes, first of all, the scenery and the dramatic; the charming thing is that there is a scene, an individual reason for the dialogues. Plato gives them an environment of reality of the place and then of the characters, of the reason that brought them together, which in itself is very lovely, open and cheerful. We are led to a place, to the plane tree in the Phaedrus (229), to the clear water of the Ilyssus, through which Socrates and Phaedrus pass, to the halls of the gymnasiums, to the academy, to a banquet. But this invention is even more particularized by external, special, accidental, particular reasons. Plato puts his thoughts into the mouths of other people, so that he himself never appears by name, thereby completely ignoring everything that is theoretical, assertive, and dogmatic, and we see no more a subject – him – as appear than in the history of Thucydides or in Homer. Xenophon sometimes lets himself appear, and sometimes he always pretends to be intentional, to justify his teaching and life by examples. With Plato everything is completely objective and vivid; it is an art to remove it far from himself, often to push it into the third or fourth person (Phaedo). Socrates is the main character, then other characters; many are stars we know: Agathon, Zeno, Aristophanes. What belongs to Socrates or Plato of what is presented in the dialogues requires no further investigation. This much is certain: we are able to fully recognize his system from Plato’s dialogues.

As regards the tone of the intercourse between the characters in these Dialogues, we find that the noblest (Attic) urbanity of well-bred men reigns supreme; the Dialogues are a lesson in refinement; we see in them the savoir faire of a man acquainted with the world. The term courtesy does not quite express urbanity; it is too wide, and includes the additional notion of testifying respect, of expressing deference and personal obligation; urbanity is true courtesy, and forms its real basis. But urbanity makes a point of granting complete liberty to all with whom we converse, both as regards the character and matter of their opinions, and also the right of giving expression to the same. Thus in our counter-statements and contradictions we make it evident that what we have ourselves to say against the statement made by our opponent is the mere expression of our subjective opinion; for this is a conversation carried on by persons as persons, and not objective reason talking with itself. However energetically we may then express ourselves, we must always acknowledge that our opponent is also a thinking person; just as one must not take to speaking with the air of being an oracle, nor prevent anyone else from opening his mouth in reply. This urbanity is, however, not forbearance, but rather the highest degree of frankness and candour, and it is this very characteristic which gives such gracefulness to Plato’s Dialogues.