Hegel über Platon 008

Parte de:

Lecciones de Historia de la Filosofía [Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie] / Primera parte: La Filosofía Griega [Erster Teil: Griechische Philosophie] / Sección Primera: de Tales a Aristóteles [Erster Abschnitt. Von Thales bis Aristoteles] / Capítulo 3: Platón y Aristóteles [Drittes Kapitel: Platon und Aristoteles] / A. Platón [A. Philosophie des Platon]

Tabla de contenidos

Vorlesungen im Atrium Philosophicum §8

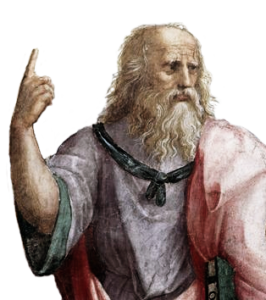

So geehrt im ganzen und besonders in Athen lebte Platon bis in die 108. Olympiade (348 v. Chr. Geb.). Er starb an seinem Geburtstage bei einem Hochzeitsschmause im 81. Jahre seines Alters.

Platons Philosophie ist uns in den Schriften, die wir von ihm haben, hinterlassen. Form und Inhalt sind von gleich anziehender Wichtigkeit. Beim Studium derselben müssen wir aber wissen, α) was wir in ihnen zu suchen haben und in ihnen von Philosophie finden können, β) und eben damit, was der Platonische Standpunkt nicht leistet, seine Zeit überhaupt nicht leisten kann. So kann es sein, daß sie uns [19] sehr unbefriedigt lassen, das Bedürfnis, mit dem wir zur Philosophie treten, nicht befriedigen können. Es ist besser, sie lassen uns im ganzen unbefriedigt, als wenn wir sie als das Letzte ansehen wollen. Sein Standpunkt ist bestimmt und notwendig; man kann aber bei ihm nicht bleiben, noch sich auf ihn zurückversetzen, – die Vernunft macht höhere Anforderungen. Ihn zum Höchsten für uns zu machen, als den Standpunkt, den wir uns nehmen müssen, dies gehört zu den Schwächen unserer Zeit, die Größe, das eigentlich Ungeheure der Anforderung des Menschengeistes nicht tragen zu können, sich erdrückt zu fühlen und darum schwachmütig von ihm sich zurückzuflüchten. Wie in der Pädagogik das Bestreben ist, die Menschen zu erziehen, um sie vor der Welt zu verwahren, d.h. sie in einem Kreise – z.B. des Comptoirs, idyllisch des Bohnenpflanzens – zu erhalten, in dem sie von der Welt nichts wissen, keine Notiz von ihr nehmen, so ist in der Philosophie zurückgegangen worden zum religiösen Glauben, so zur Platonischen Philosophie. Beides sind Momente, die ihren wesentlichen Standpunkt und Stellung haben; aber sie sind nicht Philosophie unserer Zeit. Man hätte Recht, zu ihr zurückzukehren, um die Idee, was spekulative Philosophie ist, wieder zu lernen; aber es ist Leichtigkeit, so schön zu sprechen, nach Lust und Liebe im allgemeinen von Schönheit, Vortrefflichkeit. Man muß darüber stehen, d.h. das Bedürfnis des denkenden Geistes unserer Zeit kennen oder vielmehr dies Bedürfnis haben. – Das Literarische, das Kritische Herrn Schleiermachers, die kritische Sonderung, ob die einen oder die anderen Nebendialoge echt seien (über die großen kann ohnehin nach den Zeugnissen der Alten kein Zweifel sein), ist für Philosophie ganz überflüssig und gehört der Hyperkritik unserer Zeit an.

Praelēctiōnēs in Ātriō Philosophicō §8

Platón vivió honrado en todas partes, sobre todo en Atenas, hasta el primer año de la 108ª Olimpíada (348 a. C.). Murió el día en que cumplía años, en un banquete de bodas, a los ochenta y uno de edad.1Diógenes Laercio, III, 2; Brucker, Hist. Crit. Phil., tom. I, p. 653.

Digamos ahora algo acerca del modo inmediato en que ha llegado a nosotros la filosofía de Platón, que son los escritos que de él poseemos, sin ningún género de duda uno de los más bellos regalos que la suerte nos ha legado de la antigüedad. Las obras de Platón tienen una importancia igualmente atrayente por su forma y por su contenido. Pero, para afrontar debidamente su estudio, debemos saber, de una parte, qué es lo que en ellas debemos buscar y podemos encontrar de filosofía; y, de otra parte y precisamente por ello, lo que el punto de vista de Platón no nos ofrece, sencillamente porque no podía ofrecérnoslo la época en que Platón vivió. Puede, pues, ocurrir que estas obras dejen muy insatisfecha la necesidad que a nosotros nos lleva a la filosofía; pero, después de todo, es preferible que no nos satisfagan en conjunto que no que las consideremos como algo último e inapelable. El punto de vista de Platón es un punto de vista determinado y necesario, pero no podemos empecinarnos en él ni retrotraernos a él, pues la razón tiene, hoy, exigencias superiores a las de su tiempo. Hacer de él algo insuperable, como el punto de vista en que nosotros mismos deberíamos situarnos, es una de las debilidades propias de nuestro tiempo; debilidad que consiste en no poder soportar la grandeza verdaderamente inmensa de las exigencias del espíritu humano, en sentirse agobiado por este peso y en retroceder, por ello, pusilánimemente ante él. No, es necesario estar por encima de Platón, es decir, conocer la necesidad del espíritu pensante de nuestro tiempo, o, mejor dicho, sentir esta necesidad. Así como en pedagogía algunos aspiran a educar al hombre para precaverlo contra el mundo, es decir, para que se encierre en un círculo aparte —por ejemplo, en un despacho, o viva idílicamente plantando y cultivando habas—, en el que no sepa nada de lo que pasa en el mundo ni tome conocimiento de él, así también en la filosofía se ha retornado a la fe religiosa y a la filosofía platónica.2Cfr. t. I, pp. 48. Ambos son, evidentemente, momentos que responden a su punto de vista y a su posición esenciales; pero no son, desde luego, la filosofía de nuestro tiempo. Estaría justificado el tratar de retornar a Platón para volver a aprender de él la idea de la filosofía especulativa; pero es una tontería expresarse en términos tan hermosos, a gusto y antojo del que escribe, acerca de la belleza y la excelencia de estos escritos. Sobre todo, las disquisiciones literarias del señor Schleiermacher, los sondeos críticos que se hacen para averiguar si estos o los otros diálogos secundarios son auténticos o apócrifos (pues acerca de los principales apenas dejan lugar a dudas los testimonios de los autores antiguos), son absolutamente superfluos en filosofía y nacen, en realidad, de ese espíritu hipercrítico tan característico de nuestra época.

Perge ad initium paginae huius

Lectures at the Atrium Philosophicum §8

Plato lived thus honored on the whole and especially in Athens until the 108th Olympiad (born 348 BC). He died on his birthday at a wedding feast in his 81st year.

Plato’s philosophy has been left to us in the writings that we have from him. Form and content are of equally attractive importance. When studying them, however, we must know α) what we are looking for in them and what we can find in them of philosophy, β) and precisely what the Platonic standpoint does not achieve, his time cannot achieve at all. So it can happen that they leave us very unsatisfied, cannot satisfy the need with which we approach philosophy. It is better that they leave us unsatisfied on the whole than if we want to see them as the ultimate. His standpoint is definite and necessary; but one cannot remain with it, nor return to it – reason makes higher demands. To make it the highest for us, as the standpoint that we must take, this is one of the weaknesses of our time, the greatness, the actual enormity of the demands of the human spirit, of not being able to bear it, of feeling overwhelmed and therefore weak-heartedly fleeing from it. Just as in pedagogy the aim is to educate people in order to protect them from the world, i.e. to keep them in a circle – e.g. the office, the idyllic bean planting – in which they know nothing of the world, take no notice of it, so in philosophy there has been a return to religious belief, to Platonic philosophy. Both are moments that have their essential standpoint and position; but they are not the philosophy of our time. One would be right to return to it in order to learn again the idea of what speculative philosophy is; but it is easy to speak so beautifully, according to pleasure and love, in general about beauty and excellence. One must rise above it, i.e. know the need of the thinking mind of our time, or rather have this need. – The literary, the critical aspect of Mr. Schleiermacher, the critical separation of whether one or the other of the side dialogues is genuine (there can be no doubt about the great ones anyway, according to the testimony of the ancients), is completely superfluous for philosophy and belongs to the hyper-criticism of our time.