Hegel über Platon 003

Parte de:

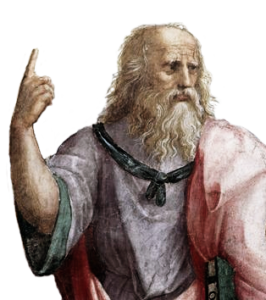

Lecciones de Historia de la Filosofía [Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie] / Primera parte: La Filosofía Griega [Erster Teil: Griechische Philosophie] / Sección Primera: de Tales a Aristóteles [Erster Abschnitt. Von Thales bis Aristoteles] / Capítulo 3: Platón y Aristóteles [Drittes Kapitel: Platon und Aristoteles] / A. Platón [A. Philosophie des Platon]

Tabla de contenidos

Vorlesungen im Atrium Philosophicum §3

Vorher haben wir seiner Lebensumstände zu erwähnen. »Platon war ein Athener, wurde im 3. Jahre der 87. Olympiade oder nach Dodwell Ol. 87, 4 (429 v. Chr. Geburt) zu Anfang des Peloponnesischen Krieges geboren, in dem Jahre, in welchem Perikles starb.« Er war 39 oder 40 Jahre jünger als Sokrates. »Sein Vater Ariston leitete sein Geschlecht von Kodros her; seine Mutter Periktione stammte von Solon ab.« Der Vatersbruder von seiner Mutter war jener berühmte Kritias (bei dieser Gelegenheit zu erwähnen), der ebenfalls mit Sokrates eine Zeitlang umgegangen war, und »einer der 30 Tyrannen Athens«, der talentvollste, geistreichste, daher auch der gefährlichste und verhaßteste unter ihnen. Dem Sokrates wurde dies besonders sehr übelgenommen und zum Vorwurf gemacht, daß er solche Schüler wie ihn und Alkibiades gehabt, die Athen durch ihren Leichtsinn fast an den Rand des Verderbens brachten. Denn wenn er sich in die Erziehung einmischte, die andere ihren Kindern gaben, so war man zur Forderung berechtigt, daß das nicht tröge, was er zur Bildung der Jünglinge tun wollte. Kritias wird mit dem Kyrenaiker Theodoros und dem Diagoras aus Melos gewöhnlich von den Alten als Gottesleugner aufgeführt. Sextus Empirikus hat ein hübsches Fragment aus einem seiner Gedichte.

Platon nun, aus diesem vornehmen Geschlechte entsprossen (die Mittel seiner Bildung fehlten nicht), erhielt durch die angesehensten Sophisten eine Erziehung, die in ihm alle Geschicklichkeiten übte, die für einen Athener gemäß geachtet wurden. »Er erhielt erst später von seinem Lehrer den Namen Platon; in seiner Familie hieß er Aristokles. Einige schreiben seinen Namen der Breite seiner Stirn, andere dem Reichtum und der Breite seiner Rede, andere der Wohlgestalt, Breite seiner Figur zu. In seiner Jugend kultivierte er die Dichtkunst und schrieb Tragödien« (wie [13] auch wohl bei uns die jungen Dichter mit Tragödien anfangen), »Dithyramben und Gesänge« (melê, Lieder, Elegien, Epigramme). Von den letzten sind uns in der griechischen Anthologie noch verschiedene aufbehalten, die auf seine verschiedenen Geliebten gehen; unter anderen ein bekanntes an einen Aster (Stern), einen seiner besten Freunde, das einen artigen Einfall enthält:

Nach den Sternen blickst du, mein Aster, o möcht’ ich der Himmel

Werden, um auf dich mit so viel Augen zu sehn.

Praelēctiōnēs in Ātriō Philosophicō §3

Pero, antes de exponer la filosofía platónica, es obligado decir algo acerca de la vida de Platón. Platón nació en Atenas en el tercer año de la 87ª Olimpíada o, según Dodwell, en la Ol. 87,4 (429 a. C.), al comienzo de la guerra del Peloponeso, en el mismo año en que murió Pericles. Tendría, según esto, 39 o 40 años menos que Sócrates. Su padre, Aristón, hacía descender su linaje del legendario rey Codro; Perictione, su madre, descendía de Solón. Era tío suyo, hermano de su madre por línea paterna, aquel famoso Critias, que había mantenido también trato con Sócrates durante largo tiempo y que era, sin duda alguna, el más inteligente, el más espiritual y, por tanto, el más peligroso y el más odiado de los Treinta Tiranos de Atenas (v. supra, pp. 73 s.). Los antiguos suelen citar el nombre de Critias al lado de los del cirenaico Teodoro y de Diágoras de Melos, entre los de los que negaban a los dioses; Sexto Empírico (Adv. Math. IX, 51-54) nos ha conservado un bonito fragmento de uno de sus poemas.

A un hombre como Platón, nacido en el seno de tan noble familia, no podían faltarle los medios necesarios para su educación. Recibió de los más prestigiosos sofistas de su tiempo una enseñanza que desarrolló en él todas las aptitudes que cumplían a un ateniense. El nombre de Platón lo recibió más tarde, de su maestro; su familia le había dado el de Aristocles. Algunos atribuían su nombre posterior a la anchura de su frente, otros a la riqueza de su lenguaje, otros a la buena apariencia de su figura.1Diógenes Laercio, III, 1-4 (Tennemann, t. I, p. 416; II, p. 190. Cultivó en su juventud el arte de la poesía y escribió tragedias —también entre nosotros suelen empezar los poetas jóvenes componiendo obras trágicas—, ditirambos y cantos. En la antología griega se han conservado algunas composiciones de esta última clase, dedicadas a diversas personas amadas por el poeta; entre ellas, un conocido epigrama dirigido a un tal Aster, uno de sus mejores amigos, en el que encontramos un ingenioso pensamiento, que, a la vuelta de los siglos, se repite en el Romeo y Julieta de Shakespeare:

Miras al cielo, ¡oh Aster! ¡Quién fuera el cielo

Para poder mirarte a ti, con sus miles de ojos!2Diógenes Laercio, III, 5, 29.

Perge ad initium paginae huius

Lectures at the Atrium Philosophicum §3

We have to consider first the circumstances of Plato’s life. Plato is an Athenian who was born in the third or fourth year of the eighty-seventh Olympiad (429 BC), the year when Pericles died, in the first phase of the Peloponnesian War. Ariston, his father, traced his lineage from Codrus. Perictione, his mother, was descended from Solon. So Plato came from one of the most respected families in Athens. His maternal great-uncle Critias, a friend of Socrates, was one of the Thirty Tyrants, the most talented and clever of them and hence the one most dangerous and most hated; a poem found in Sextus Empiricus accuses him of atheism. Plato was born into this family and had the very best resources available for his education; he received instruction in all of the skills befitting a free Athenian. His name was in fact Aristocles, and only later on did he acquire the name Plato, owing to his broad forehead or to his sturdy body X1X. In his youth he studied poetics in particular and he wrote tragedies—just as our young poets today start out writing a tragedy—and also elegies and epigrams; a few of the latter, which are still extant, contain charming notions. For instance, one addressed to a beloved youth, Ἀστήρ, reads: “To the stars thou look’st, mine Aster. Oh, would that I were the sky, with as many ayes to gaze on thee.” We find the same thought expressed in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet X2X.

Some clarifications

X1X

Diogenes Laertius (De vitis [‘On the Lives and Opinions of the Philosophers’] 3.2-3), drawing upon Apollodorus, puts Plato’s birth in the eighty-eighth Olympiad; see Lives of Eminent Philosophers, trans. R. D. Hicks, 2 vols. (Loeb Classical Library; Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1925, 1938), i. 277-9. Hegel had various editions of Diogenes Laertius in his library, including several with annotations on the text by Henricus Stephanus [Henri Estienne], Isaac Casaubon, and others. To arrive at the birth date he gives, Hegel may have counted back eighty-one years from the year of Plato’s death (see n. 21 just below). Or he may have taken this date from Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann, Geschichte der Philosophie, 11 vols. (Leipzig, 1798-1819), ii. 190; cf. W. xiv. 171-2, as well as references to Plato’s birth occurring in the same year as the death of Pericles (429 BC), found in Tennemann (i. 416) and this passage from Diogenes. Many today put Plato’s birth in 427 BC. Hegel follows Tennemann (ii. 190), not Diogenes, in having Ariston himself claim descent from Codrus. W, xiv, 171-2 adds a third possible reason (taken from Diogenes, 3.4) for Plato’s name—his broad powers of speech. Hegel’s comment on Critias reflects the account of Xenophon; see p. 145 above. W, xiv. 171-2, citing Sextus Empiricus, situates Critias in the company of diverse atheists, including those such as Euhemerus who regard the idea of God as a human invention. According to Sextus (Adversus mathematicos 9.50-4), Critias said that ‘the ancient lawgivers invented God as a kind of overseer of the right and wrong actions of men, in order to make sure that nobody injured his neighbors privily through fear of vengeance at the hands of the Gods’; see Sextus Empiricus, trans. R. G. Bury, 4 vols. (Loeb Classical Library; New York and London, 1933-49), iii, 28-33. This passage contains the poem expressing this atheism and attributes it to Critias, but not in an accusatory manner.

X2X

Diogenes Laertius states that Plato took up painting and wrote dithyrambs, lyric poems and tragedies (Lives 3.5; Hicks, i. 280~1); he also presents the epigram to Aster (3.29; Hicks, i. 302-3), See Romeo and Juliet, Act I, Scene i, lines 57-64. Hegel’s library contained two German versions of Shakespeare: the revised edition of Johann Joachim Eschenberg’s translation (Mannheim, 1779)—see ix. 278; the edition of Johann Heinrich Voss and his sons, Heinrich and Abraham (Leipzig, 1818)—see i. 251-2.