What is Political Philosophy? III 021

Parte de:

¿Qué es la Filosofía Política? / III. Las soluciones Modernas

Por Leōnardus Strūthiō

Tabla de contenidos

Leōnardī Strūthiī verba

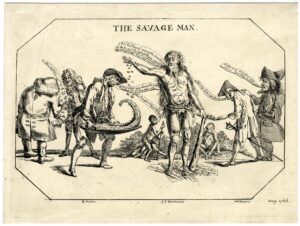

Rousseau was not unaware of these difficulties. They had been caused by the exinanition1See exinanition in the Oxford English Dictionary. of the notion of human nature and ultimately by the turn from man’s end to man’s beginning. Rousseau had accepted Hobbes’s anti-teleological principle. By following it more consistently than Hobbes himself had done, he was compelled to reject Hobbes’s scheme or to demand that the state of nature—man’s primitive and pre-social condition—be understood as perfect, i.e., as not pointing beyond itself toward society. He was compelled to demand that the state of nature, man’s beginning, become the goal for social man: only because man has drifted away from his beginnings, because he has thus become corrupted, does he need an end. That end is primarily the just society. The just society is distinguished from the unjust society by the fact that it comes as close to the state of nature as a society possibly can: the desire determining man in the state of nature, the desire for self-preservation, is the root of the just society and determines its end. This fundamental desire which is at the same time the fundamental right, animates the juridical as distinguished from the moral: society is so far from being based on morality that it is the basis of morality; the end of society must therefore be defined in juridical, not in moral terms; and there cannot be an obligation to enter society (or the social contract cannot bind “the body of the people”). Whatever the meaning and the status of morality may be, it certainly presupposes society, and society, even the just society, is bondage or alienation from nature. Man ought therefore to transcend the whole social and moral dimension and to return to the wholeness and sincerity of the state of nature. Since the concern with self-preservation compels man to enter society, man ought to go back beyond self-preservation to the root of self-preservation. This root, the absolute beginning, is the feeling of existence, the feeling of the sweetness of mere existence. By giving himself to the sole feeling of his present existence without any thought of the future, by thus living in blessed oblivion of every care and fear, the individual senses the sweetness of all existence: he has returned to nature. It is the feeling of one’s existence which gives rise to the desire for the preservation of one’s existence. This desire compels man to devote himself entirely to action and thought, to a life of care and duty and misery, and therewith cuts him off from the bliss which is buried in his depth or origin. Only very few men are capable of finding the way back to nature. The tension between the desire for the preservation of existence and the feeling of existence expresses itself therefore in the insoluble antagonism between the large majority who in the best case will be good citizens and the minority of solitary dreamers who are the salt of the earth. Rousseau left it at that antagonism. The German philosophers who took up his problem thought that a reconciliation is possible, and that reconciliation can be brought about, or has already been brought about, by History.

Hispānice

Estas dificultades no pasaron desapercibidas a Rousseau. Habían sido causadas por el vaciamiento de la noción de naturaleza humana y, en última instancia, por el cambio de énfasis de los fines del hombre hacia los comienzos del hombre.2 Estos «comienzos» son aclarados por el prof. Strūthiō como: «las carencias elementales o de los impulsos —deseos— que en realidad determinan a todos los hombres la mayor parte del tiempo», en oposición a unos «principios» que expresan «la perfección humana o su fin, cuyo deseo determina en realidad solo a unos pocos hombres y de ninguna manera la mayor parte del tiempo», vide supra III 015. Rousseau había, pues, aceptado el principio antiteleológico de Hobbes. Al seguir dicho principio de manera más consistente que el propio Hobbes, se vio obligado a rechazar el esquema del inglés o a exigir que el estado de naturaleza —la condición primitiva y presocial del hombre— se entendiera como perfecto, es decir, como algo que no apunta más allá de sí mismo, que no conlleva a la formación de la sociedad. Con ello se vio forzado a exigir que el estado de naturaleza, los comienzos del hombre, se convirtiesen en la meta del hombre social: es unicamente debido a que el hombre ha sido apartado de sus comienzos, y con ello se ha corrompido, por lo que requiere de un fin. Dicho fin es fundamentalmente la sociedad justa. La sociedad justa se distingue de la sociedad injusta por el hecho de que se acerca al estado de naturaleza tanto como puede hacerlo una sociedad. El deseo que determina al hombre en el estado de naturaleza, el deseo de autoconservación, es pues la raíz de la sociedad justa y determina su fin. Este deseo fundamental, que es al mismo tiempo el derecho fundamental, anima a lo jurídico en tanto que distinto de lo moral: La sociedad está tan lejos de estar basada en la moralidad que termina ella misma siendo la base de la moralidad. Por tanto, el fin de la sociedad debe definirse en términos jurídicos, no morales; y no puede haber una obligación de entrar en la sociedad (esto es, el contrato social no puede vincular al «cuerpo del pueblo»). Cualquiera que sea el significado y el estatus de la moralidad, cierto es que presupone la sociedad, y la sociedad, incluso la sociedad justa, es esclavitud, entendida como alienación de la naturaleza. El hombre debe, por tanto, trascender toda la dimensión social y moral y volver a la totalidad y sinceridad del estado de naturaleza. Debido a que el deseo de conservación obliga al hombre a entrar en sociedad, el hombre debe remontarse más allá de la conservación y aproximarse a la raíz de la conservación. Esta raíz, el comienzo absoluto, es el sentimiento de la existencia, el sentimiento de la dulzura de la mera existencia. Al entregarse únicamente al sentimiento de su existencia presente sin pensar en el futuro, al vivir así en un feliz olvido de toda preocupación y temor, el individuo siente la dulzura de toda existencia: ha regresado a la naturaleza. Es el sentimiento de la propia existencia lo que da lugar al deseo de conservación de la propia existencia. Este deseo obliga al hombre a consagrarse por completo a la acción y al pensamiento, a una vida de cuidados, deberes y miserias. Esto lo separa de la dicha que está sepultada en lo más profundo de su origen. Sólo muy pocos hombres son capaces de encontrar el camino de regreso a la naturaleza.

ARCĀNA IMPERIĪ ***