What is Political Philosophy? I 024

Parte de:

¿Qué es la Filosofía Política? / I. El problema de la Filosofía Política

Por Leōnardus Strūthiō

Tabla de contenidos

Leōnardī Strūthiī verba

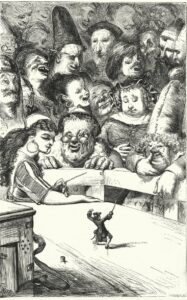

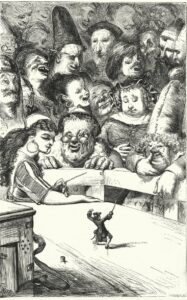

(3) The belief that scientific knowledge, i.e., the kind of knowledge possessed or aspired to by modern science, is the highest form of human knowledge, implies a depreciation of pre-scientific knowledge. If one takes into consideration the contrast between scientific knowledge of the world and pre-scientific knowledge of the world, one realizes that positivism preserves in a scarcely disguised manner Descartes’ universal doubt of pre-scientific knowledge and his radical break with it. It certainly distrusts pre-scientific knowledge, which it likes to compare to folklore. This superstition fosters all sorts of sterile investigations or complicated idiocies. Things which every ten-year-old child of normal intelligence knows are regarded as being in need of scientific proof in order to become acceptable as facts. And this scientific proof, which is not only not necessary, is not even possible. To illustrate this by the simplest example: all studies in social science presuppose that its devotees can tell human beings from other beings; this most fundamental knowledge was not acquired by them in classrooms; and this knowledge is not transformed by social science into scientific knowledge, but retains its initial status without any modification throughout. If this pre-scientific knowledge is not knowledge, all scientific studies, which stand or fall with it, lack the character of knowledge. The preoccupation with scientific proof of things which everyone knows well enough, and better, without scientific proof, leads to the neglect of that thinking, or that reflection, which must precede all scientific studies if these studies are to be relevant. The scientific study of politics is often presented as ascending from the ascertainment of political “facts,” i.e, of what has happened hitherto in politics, to the formulation of “laws” whose knowledge would permit the prediction of future political events. This goal is taken as a matter of course without a previous investigation as to whether the subject matter with which political science deals admits of adequate understanding in terms of “laws” or whether the universals through which political things can be understood as what they are must not be conceived of in entirely different terms. Scientific concern with political facts, relations of political facts, recurrent relations of political facts, or laws of political behaviour, requires isolation of the phenomena which it is studying. But if this isolation is not to lead to irrelevant or misleading results, one must see the phenomena in question within the whole to which they belong, and one must clarify that whole, i.e., the whole political or politico-social order. One cannot arrive, e.g., at a kind of knowledge of “group politics” which deserves to be called scientific if one does not reflect on what genus of political orders is presupposed if there is to be “group politics” at all, and what kind of political order is presupposed by the specific “group politics” which one is studying. But one cannot clarify the character of a specific democracy, e.g., or of democracy in general, without having a clear understanding of the alternatives to democracy. Scientific political scientists are inclined to leave it at the distinction between democracy and authoritarianism, i.e., they absolutize the given political order by remaining within a horizon which is defined by the given political order and its opposite. The scientific approach tends to lead to the neglect of the primary or fundamental questions and therewith to thoughtless acceptance of received opinion. As regards these fundamental questions our friends of scientific exactness are strangely unexacting. To refer again to the most simple and at the same time decisive example, political science requires clarification of what distinguishes political things from things which are not political; it requires that the question be raised and answered “what is political?” This question cannot be dealt with scientifically but only dialectically. And dialectical treatment necessarily begins from pre-scientific knowledge and takes it most seriously. Pre-scientific knowledge, or “common sense” knowledge, is thought to be discredited by Copernicus and the succeeding natural science. But the fact that what we may call telescopic-microscopic knowledge is very fruitful in certain areas does not entitle one to deny that there are things which can only be seen as what they are if they are seen with the unarmed eye; or, more precisely, if they are seen in the perspective of the citizen, as distinguished from the perspective of the scientific observer. If one denies this, one will repeat the experience of Gulliver with the nurse in Brobdingnag and become entangled in the kind of research projects by which he was amazed in Laputa.

Hispānice

(3) La creencia de que el conocimiento científico —es decir, la clase de conocimiento que posee, o aspira a poseer, la ciencia moderna— es la más elevada forma del conocimiento humano implica una devaluación del conocimiento precientífico. Si tomamos en consideración el contraste entre el conocimiento científico del mundo y el conocimiento precientífico del mismo, nos daremos cuenta que el el positivismo mantiene, de una manera a penas disfrazada, la duda universal de Descartes respecto al conocimiento precientífico y su radical ruptura con él. El positivismo, ciertamente, desconfía de todo conocimiento precientífico, al que gusta de comparar con el folclor. Esta superstición —el folclor— alberga toda clase de investigaciones estériles o complicadas estupideces. Cosas tales como las que incluso un niño de diez años, con inteligencia promedio, sabe que deben ser consideradas en el conjunto de aquellas que necesitan una prueba científica para que puedan ser aceptadas como hechos. Dicha prueba científica que, por otra parte, no sólo no es necesaria, sino que ni siquiera es posible. Para ilustrar esto con el ejemplo más simple: todos los estudios de ciencia social presuponen que aquellos que los realizan son capaces de diferenciar a los seres humanos de los demás seres; este conocimiento fundamental —el más fundamental—no lo adquirieron en las aulas, ni ha sido convertido en conocimiento científico por la ciencia social, sino que mantiene su estatus inicial sin modificación alguna en todo el proceso. Si este conocimiento precientífico no fuera tal conocimiento, todos los estudios científicos, que se apoyan o están incluidos en él, carecen también de dicho carácter científico. La preocupación por buscar una prueba científica para hechos que todo el mundo conoce suficientemente sin necesidad de tal prueba conduce al desprecio de pensamientos o reflexiones que deben preceder a todos los estudios científicos si es que esos estudios aspiran a relevancia alguna. Frecuentemente se suele presentar el estudio científico de la política como un proceso de ascenso desde la comprobación de los «hechos» políticos, esto es, de lo que ha sucedido hasta nuestros días en política, hasta la formulación de «leyes» cuyo conocimiento permita la predicción de futuros acontecimientos políticos. Este objetivo se da por sentado sin que se investigue previamente si el objeto de estudio de la ciencia política admite comprensión adecuada en términos de «leyes» o si los universales a través de los cuales se pueden comprender las cuestiones políticas tal como son no deben concebirse en términos completamente diferentes. La aproximación científica a los hechos políticos, a las relaciones, a las recurrentes relaciones de estos hechos, o a las leyes que rigen el comportamiento político exige la contemplación aislada del fenómeno que estamos estudiando. Pero, para que este aislamiento no nos conduzca a resultados irrelevantes o engañosos, debemos de contemplar los fenómenos que estudiamos dentro del conjunto al que pertenecen; esto es, debemos explicar la totalidad del orden político o político-social. No se puede llegar, por ejemplo, a un tipo de conocimiento sobre «política de grupos» que merezca ser llamado científico sin reflexionar en qué tipo de ordenes políticos se presuponen para que exista uno tal como «política de grupos»; y, qué tipo de orden político presupone la «política de grupos» específica que se está estudiando. Menos aún se puede aclarar el carácter de una democracia específica, por ejemplo, o de la democracia en general, sin tener una comprensión clara de las alternativas a la democracia. Los científicos políticos con enfoque científico están inclinados a reducir este problema a la distinción entre democracia y autoritarismo, o sea, convierten en absoluto el orden político dado para que no existan más posibilidades que dicho orden y su contrario. El enfoque científico tiende a llevar a descuidar las cuestiones fundamentales y, con ello, a aceptar irreflexivamente la opinión previamente recibida. En lo que se refiere a estas cuestiones fundamentales, nuestros amigos de la exactitud científica se muestran extrañamente imprecisos. Volviendo a citar el ejemplo más sencillo, y al mismo tiempo el más relevante, la ciencia política exige que se aclare lo que distingue a los asuntos políticos de los que no lo son; exige que se plantee y responda la pregunta «¿qué es político?». Esta cuestión no puede abordarse científicamente, sino unicamente dialécticamente. Este tratamiento dialéctico parte necesariamente del conocimiento precientífico y se lo toma muy en serio. Resulta algo común creer que el conocimiento precientífico, o el conocimiento del «sentido común», ha sido desacreditado por Copérnico y las ciencias naturales que lo sucedieron. Pero el hecho de que lo que podríamos llamar conocimiento telescópico-microscópico sea muy fructífero en ciertas áreas no nos autoriza a negar que hay cosas que sólo pueden verse como lo que son si se las ve con ojos desarmados; o, más precisamente, si se las ve desde la perspectiva del ciudadano, a diferencia de la perspectiva del observador científico. Si uno niega esto, repetirá la experiencia de Gulliver con la nodriza en Brobdingnag y se verá enredad en el tipo de proyectos de investigación que lo asombraron en Laputa.

ARCĀNA IMPERIĪ ***